DUBLIN ACCENTS

People

Dublin is the capital of the Republic of Ireland and its largest city. It’s a very old city and a busy port city. It has been at the center of the country’s long and troubled history with England and has had ongoing linguistic interactions with that nation. In fact, English has been spoken in Dublin since the 12th Century and the Dublin version of English has been and continues to be influenced by the speech of England, and particularly London.

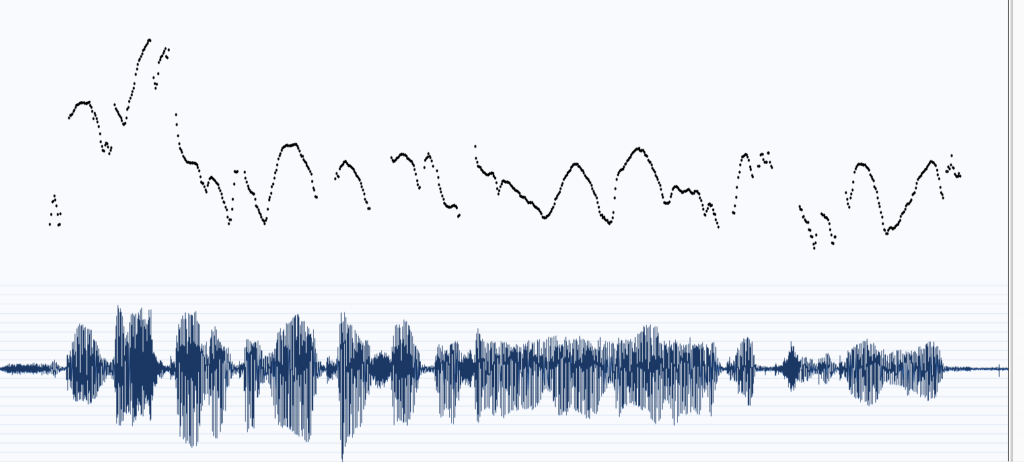

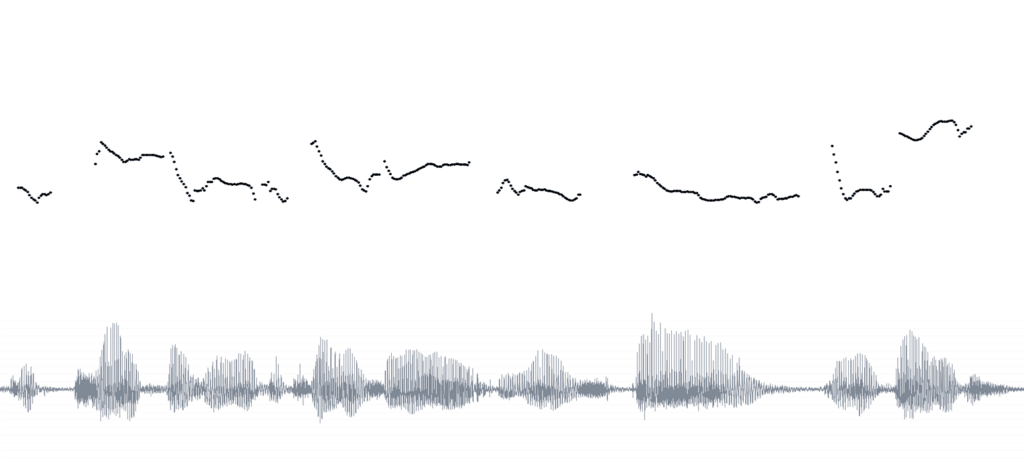

The linguist Raymond Hickey has described three main varieties of Dublin Accent: Local, Mainstream, and Fashionable. Our characters will tend to exemplify the first two. The Local accent is more strongly associated with the North Side and with working class toughness. Here’s an example of the Local variety:

The Mainstream variety is a bit less localized. It’s more prevalent in the South Side, but it also identifies a person with a larger Irish identity.

Here’s an example of a blend of Mainstream and local:

Posture

By “Oral Posture” I mean the general shape of the vocal tract, its pattern of tensions and tendencies that make the sounds of an accent comfortable and natural to perform. The Dublin oral posture involves a comparatively open jaw, and a high, spread tongue position. This accent like all Irish accents is rhotic, meaning that /r/ is pronounced after vowels. This makes it similar to American oral posture, but while there is certainly a braced tongue position and retroflex tongue tip, but it differs from American rhoticity which can involve tongue root retraction. This feels like more of a lateral motion.

It’s important though, to look for ways that these shapes form a useful, but nearly unconscious behavioral feedback loop rather than a rigid and immoveable tension pattern. In other words, be easy with it.

Prosody

Irish melody is generally more varied than in the US, but Dublin participates less in this tendency. It’s often useful to experiment with increased pitch variety, including a strong upward inflection at the ends of phrases, and then relax away from this tendency to find the more monotone, falling, and clumped pattern of Dublin speech.

Here are couple of examples to give a sense of this pattern:

You’d be lucky if you could run two feet, there were so many young boys on the pitch at the time, you know.

The Temple here at the King’s Inn was our playground.

Pronunciation: Vowels

MOUTH → ɛ̈ʊ̜̆

The starting point of this diphthong is much more closed, and there is some unrounding of the second sound. This makes MOUTH one of the most striking features of the accent.

STRUT → ʊ

The STRUT vowel that we might realize as /ʌ/ is quite rounded in Dublin

LOT⚭CLOTH⚭THOUGHT → ~ ɒ̜

The ‘rounded’ back vowels LOT, CLOTH, and THOUGHT can be a source of confusion in many accents. Californians tend to merge all three sets to an unrounded /ɑ/, while New Yorkers tend to make LOT unrounded, and round CLOTH and THOUGHT.

Generally, Irish speakers will follow the first tendency, but Dubliners usually do a bit of rounding on all three, but you can hear some speakers making a distinction (marked by rounding) between LOT and CLOTH/THOUGHT

GOAT → o ~ ʌʊ̯

. Unlike the usual realization of this sound in other parts of Ireland, the Local Dublin accent renders GOAT as a diphthong [ɡʌʊt]

Listen to this example from Tipperary, which lies to the Southwest of Dublin:

And then compare it to this Dublin example:

Here’s an example from Glen Hansard:

Finally, here’s a young female Dubliner:

FACE → ëɪ̯ ~ e

This is another example of a Dublin sound that’s slightlydifferent from other Irish accents and closer to American accents. Whereas Irish accents use a monophthongal [e], Dublin uses a diphthong [eɪ ]. The first part of that diphthong is more centralized or perhaps more open than an American FACE vowel, but it’s awfully similar.

TRAP ⚭ BATH → æ̞

American accents generally make no distinction between these two categories of vowel sounds: TRAP and BATH. Irish accents tend to follow this same pattern, merging both sounds into an /æ/ of some sort. Dublin’s associations with London tend to preserve the distinction. It is a subtle difference and not all speakers maintain it.

The TRAP vowel is more open than in Cork, and is realized usually as [æ̞].

The BATH vowel is slightly more open , moving in the direction of [aː]

Here’s an example of Glen Hansard saying the words “afterwards” and “Van”

As a bonus, the words “any” and “many” use an /æ/ vowel rather than /ɛ/

PRICE ~⚭~ PRIDE → æ̞

Raymond Hickey, who collected these samples, uses PRICE and PRIDE to mark a split between the pronunciations [pɹaɪ̯s] and [pɹɑɪ̯d] but I think these sound files show both of these words as closer to [ʌɪ̯] or even [ɒɪ̯]. So let’s call this a “merger maybe”.

Pronunciation: Rhoticity

Irish accents are largely rhotic, and this should be easy for an American to hear and to reproduce. Listen for the /r/ sounds (both before and after vowels)

These are samples of Glen Hansard telling a story about Van Morrison.

START → aɚ̯

In addition, in words like START In Dublin speech, the starting point of this diphthong tends to be closer to TRAP than in the American pronunciation

Pronunciation: Consonants

THink θ → t̪

The /θ/ phoneme is usually realized as [t] and sometimes as a dentalized plosive [t̪] in the local variety. In Mainstream Dublin, it is more likely to remain [θ]

breaTHe ð → d̪

The same applies to the voiced form /ð/ with its realizations being [d] [d̪] [ð]

geT → t ~ tˢ ~ ʔ̚

Dubliners can sometimes use a fricative release – [ts]. This seems to happen most in final positions in words. There is another strong tendency, however to drop the sound entirely in these positions, perhaps substituting it with a glottal stop.

Look ≠ raiL → l not ɫ

Like most Americans, Irish speakers use a “clear” or “slender ” /l/ in initial positions. After a vowel, we might expect a “velarized” or “thick” /ɫ/ as in other varieties of English, but here, the “slender l” is retained