PEOPLE

In Knight-Thompson Speechwork, we start our work on an accent by focusing on People. We start here because accent is a cultural behavior, and culture is something made by, and made of people. We want to start our work with an understanding how our perception of accent aligns with our perceptions of a person’s web of belonging, and our understanding how the patterns that emerge from someone’s speech tell a story of who that person is and where they come from. We also start here because it serves as a reminder that the people we represent with our performances are people, and thus deserving of our empathy and care. This isn’t a trivial step, but a vital part of “getting right with” the people whose accents we wish to wear.

Notice first that this breakdown is entitled “A German Accent.” It isn’t “The German Accent”. There are many varieties of German, and many ways that the speakers of any particular variety will tackle English, and every L1 speaker of some German who speaks their own version of English will be variable in their speech from day to day and moment to moment. This can’t be an absolute description of each idiolect, but it can, perhaps more helpfully, be a guide to experiencing the sonic fingerprint shared by many speakers of German when they speak in English.

An important step in connecting with the People aspect of an accent is what we might think of as the “bias check”. Bias, of course, is the tendency of human minds to bend our perceptions towards preconceived notions of the world. The word “check” has an interesting cluster of meanings. It could mean “look at” or “hold back” or in the context of airline travel it means putting away for safe keeping as we “check” our baggage. So let’s start by taking an honest look at the associations we might hold, or which we may have encountered regarding German accents.

A UCI alumna Madison Scott (co-founder of the 30/60 group) described this as our “cultural imagining” of what Germany and Germans are like. We might list sexy beer maids, dancing men in lederhosen, humorless spinsters, strict automotive engineers or (saving the worst for last) Nazis. All of these associations percolate through the stories we tell and consume in film, television and fiction.

In their 1943 book “Foreign Dialects,” Lewis and Marguerite Herman described German (the German language and German accented English) as follows:

The lilt of the German dialect is slow, plodding and pedestrian. Its lengthened vowel sounds are the result of deliberate thought processes evolving methodically into sonant speech. It is only in these vowel glides-which do not rise or fall but are simply attenuated on the same note–that the German dialect achieves a semblance of lilt. On the whole, the speech is guttural with little music to be found in these harsh tones. It would be only a rabid Germanophile who could find “beautiful music” in the rasping gutturalness of “Ach!,” “nacht,” and “buch” with their gargled “ch’s.” The absence of long words in the dialect-although the language abounds in long, windy words-tends to brighten the plodding lilt that borders on the monotonous.

That is clearly a point of view influenced by the biases we might expect when describing a nation with which we were at war. It’s also a vivid example of how easily our thinking about accent can become freighted with negative attitudes toward people. I wouldn’t say that anti-German sentiments are currently a large social problem in the United States, but the relics of those attitudes are still available to our imaginations, and it’s important to be alert to them lest they lead us astray.

Another piece of cultural contextualization that we need to tackle with this accent is that it is an L2 accent. That is, it emerges as a consequence of German speakers coming to English as a second language. L2 accents. This means that we might gain some experience of what it’s like for such a speaker if we spend some time investigating the German language. Listen to these short phrases and then repeat them.

It’s worth noting that German and English are both Germanic languages, and there are numerous cognates shared between the two:

| alle | alt | Bruder | denken | frei | Freitag | geboren | Glück | Gott |

| all | old | brother | think | free | Friday | born | luck | God |

| gut | Haus | Hier | nächste | Politik | sehen | tanzen | Tourist | wille |

| good | house | here | next | politics | see | dance | tourist | will |

This is not to say that German speakers always pronounce an English word exactly like their German cognate, though they may be influenced by the similarity. What’s even more important, though, is that a lifetime of speaking German has accustomed speakers to a particular configuration of articulators that remains the most comfortable setting of the vocal tract even when speaking English. We call this Posture.

POSTURE

German utilizes more consonants articulated in the back of the mouth and more movement of the lips between lip corner protrusion and retraction than American English. The word “buch”( pronounced /bux/) gives a good sense of the oral posture. The corners of the mouth can be compressed against the canine teeth, even during lip-rounded vowels. The jaw is held higher than in most American accents, and tends to be held more still. Without the American English tendency towards bracing the sides of the tongue against the molars, German oral posture holds the dorsum flatter. When you reach the section on the phoneme /r/ below, you will gather some more data on this aspect of the posture.

The video below is playing at slow speed, and it defaults to mute, You can come back later and listen to the sounds made by those movements.

Focus on the movements you see, and perhaps you can follow along with your own vocal tract.

Now let’s watch the video at full speed.

And here are a couple of male voices narrating books. Extra points if you can identify the books!

PROSODY

In listening to the videos above, you may have already begun to perceive a rhythmic and melodic texture to the German language.

We call this texture prosody. In fact, this term covers a much broader range of music-like properties of speech. The word derives from the Greek προσῳδίᾱ : (pros = through + ōidē = song) and in its most general sense, it refers to the aspects of language that can be described musically. For our purposes, prosody is the part of accent that we recognize through its particular musical signature.

German tends to have a flatter pitch profile than other European languages. For example, differences in pitch range, and abruptness of pitch change can be useful in distinguishing German accents from French. German sentences also have a different word order and can lead to a pattern in English of an emphatic downward intonation at ends of sentences. Similarly, German speakers will sometimes significantly lengthen the vowel in the stressed syllable of a multisyllabic word. This is particularly true towards the end of a sentence.

Focusing on a few characteristic patterns is a good way to get some handholds to help you maintain the prosodic texture.

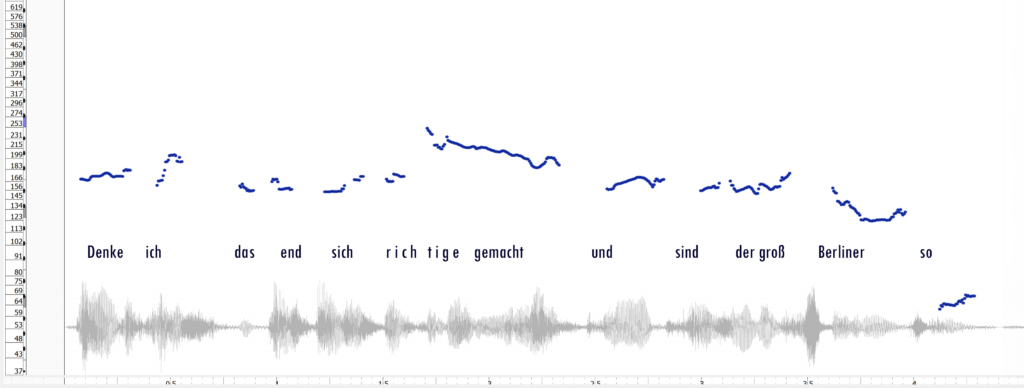

Listen to this German speaker and compare the image below with the audio:

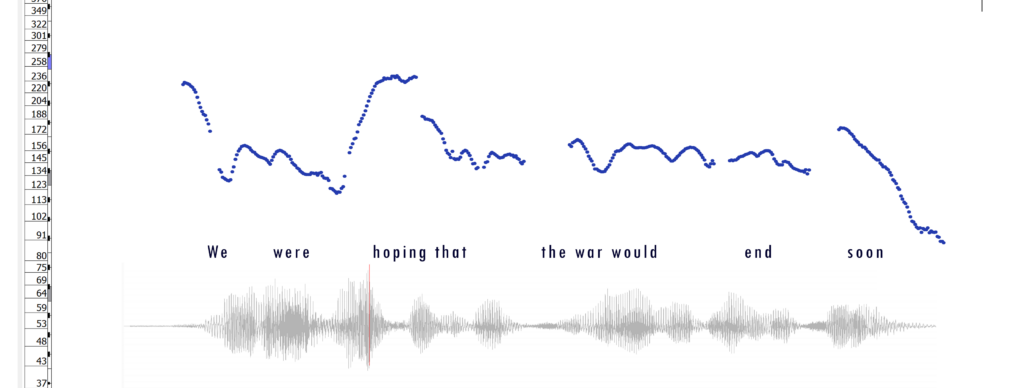

And here’s a pattern in English:

Despite the strong downward pitch pattern, it’s also common to hear a rising pitch at the ends of phrases reminiscent of “uptalk” (HRT) in English:

PRONUNCIATION

Any accent arising from speaking a second language will be variable. These pronunciation targets are only a starting place to be supplemented with listening to samples that match your character.

VOWEL FEATURES

The chart below depicts standard German vowel phonemes in their approximate positions on the vowel space. Think of this as the inventory of comfortable vowels for a German speaker. When confronted with similar vowels in English, it’s convenient for the German speaker to use a corresponding vowel from their own inventory rather than precisely matching the English version. That’s how second language accents work.

FACE → eː

In words where an English speaker would use /eɪ̯/ (FACE words) German speakers are likely to replace this with a pure vowel /eː/. There are dialects of German which use a diphthong much like the English version, so this tendency isn’t universal. In multisyllabic words like “situation’ the lengthening of the stressed vowel can be quite distinctive.

LISTEN

PRACTICE

Maybe if you waited to for Amy to explain the situation

GOAT → oː

A similar situation occurs with GOAT vowels. The English diphthong will often be replaced with the German monophthong /o/.

LISTEN

PRACTICE

The ogre’s home was mostly composed of old bones.

GOOSE → uː FLEECE→ iː

If you speak a dialect of English that realizes GOOSE and FLEECE as diphthongs, this vowel target will seem like the same sort of thing as the previous features. The German version will be tenser (more to the outer edges of the vowel chart, and will be realized as a monophthong. The German vowel may also be longer.

LISTEN

PRACTICE

Have you seen that new movie? “The Youthful Beasts” ?

TRAP (BATH) → a

This can be a very complex landscape of sounds to navigate. First, we have the differences in the way varieties of English distribute these sounds. American English generally has a single vowel phoneme (/æ/) for TRAP or BATH words where speakers of RP make a distinction, pronouncing TRAP words with /æ/, and BATH words with /ɑ/ The nearest equivalents of these in German are /a/ and /ε/ vowels, and since the categories and sounds don’t match well, the result is often a free for all with American English TRAP (BATH) words getting treated as either /a/ or /ε/.

LISTEN

After a while… what happened? The German batteries opened up.

After a while… what happened? The German batteries opened up.

PRACTICE

After that last band practice, Alex had to ask himself if anything actually mattered.

FOOT → ʊ̹ ~ u

German and English have many cognate words and there are several common words that fall within this vowel category: foot (Fuß), book (Buch), good (gut). This can be enough to lead the German speaker to see the English /ʊ/phoneme as a version of the German /u/. In addition, American realizations of the /ʊ/ vowel can be quite centralized and unrounded. The German realizations are rounder and tenser

LISTEN

PRACTICE

Look, you’re a nice woman, and a good football player, but you shouldn’t be writing cookbooks.

STRUT → ɐ ~ a ~ ɑ̽

The words in English that we categorize as STRUT words, like bus, lust, shut, run, etc., are usually realized in American English somewhere in the range of [ə] to [ɐ]. German does have a phoneme they realize as [ɐ], but they use it in words ending in “-er” like Messer, Zimmer, Sänger, or… ernährungswissenschaftler. German and English share cognates like bus (= Bus), and lust (= Lust), but those German words are pronounced with [ʊ]. Confused yet? A German speaker coming to English might also find themselves occasionally confused, but generally speaking they can grok that these English short u words are meant to be pronounced with a central vowel, and they tend to target the most open version of that vowel.

- If you want to look into the German and Hebrew origins of the word schwa check this out .

LISTEN

PRACTICE

Rhoticity

Because of the back position of the German /r/, it is common for “postvocalic r” to be dropped or pronounced very lightly. Since this corresponds to some dialects of English, it is likely to remain as a strong feature of any German accent. Alternatively, some speakers use a strongly braced /r/ in these positions. It’s useful to begin by practicing a uvular trill /ʀ/, and then allowing the gesture to relax until the resulting sound is more like vowel than a consonant.

| NEAR | SQUARE | START | NORTH | CURE | lettER |

| nɪ.ɐ | skwɛ.ɐ | staːt | nɔ.ɐθ | kçu.ɐ | lɛtɐ |

In English, historical accent changes have merged several distinct pronunciations into one which we group under the name of NURSE vowels, pronounced with an /ɚ/ vowel. German maintains more distinctions in words where a vowel is followed by /r/ and this provides German speakers with more options, and more reasons to expect English spelling to offer clues to pronunciation. Here are some possible correspondences between German and English NURSE vowels:

| German word | German Pronunciation | English Translation | Similar English word | Possible Realization |

| Lehren | ˈleːʁɐ | teach | learn | lɛɐ̯n |

| nervös | nɛɐ̯ˈvøːs | nervous | nervous | ˈnɛɐ̯v.əs |

| nur | nuːɐ̯ | only | nurse | nɵs |

| dir | dɪɐ̯ | you | dirt | dɪ̞ɐ̯t |

| Mörder | ˈmœʁdɐ | murderer | murder | ˈmœɚdɐ |

| Wort | vɔʁt | word | word | w̪œd̥ |

LISTEN

PRACTICE

Greta Miller heard there were fierce and marvelous forces at work here.

The three dots above mark a shift from vowel characteristics to consonant characteristics. You may well want to mount an argument that the previous section on Rhoticity was about consonants. That will be a productive discussion for us to have … later.

For now:

CONSONANT FEATURES

Rest /r/ # __V→ ʀ ~ ʁ ~ ɹ

As in English, the /r/ phoneme can behave differently before a vowel and after it. The German /r/ is most often made as a uvular fricative but can also be realized as a uvular or even an alveolar trill. Speakers with more fluency in English will more closely match the English alveolar approximant, but when targeting American English a German speaker could also overshoot the mark and make a particularly strongly braced /r/.

PRACTICE

Reinhard arose from his brief rest aware of an increased freedom.

beLL /ɫ/ # V__→ l

In English, a distinction is made between /l/ occurring before vowels (the ‘slender’ l) and /l/ following a vowel (the ‘thick’ l). German uses the same, ‘slender’ /l/ in both positions, and this is frequently carried into English.

LISTEN:

PRACTICE:

Well Phil, if it helps you feel better … we’re all a little older.

THink /θ/ → t ~ ʦ ~ s

THis /ð/ → d ~ ʣ ~ z

English is weird. It’s part of a small percentage of world languages that use a voiced or unvoiced dental fricative consonant. If your first language (L1) lacks these consonants, as German does,,, you’re gonna have to fake it. That approximation of the consonant may be more or less off target.

LISTEN:

PRACTICE:

The thing about this theatrical methodology is that my mother never bothered with it.

Wide /w/ → v ~ʋ

View /v/ → f ~ v̥

The letter W in German is pronounced /v/. German speakers encountering words with this spelling can easily make the error of pronouncing it with the German realization, especially in cognates such as “word” (Wort) or “world” (Welt) or “wide” (weit). Some speakers use the labiodentals approximant /ʋ/. As a speaker grows more comfortable in English, something closer to /w/ can be achieved. And while we’re dealing with spelling, the letter V in German is pronounced /f/. The Volkswagen, for example, is pronounced /fɔlksvaɡən/. German speakers can sometimes make the error of applying this pronunciation to English words, or treating all Vs and Ws in English words as a free-for -all. The letter F, however, is also pronounced /f/. This means that the word “frau” and the word “vau” both begin with an /f/ sound. Are you having fun yet?

LISTEN:

PRACTICE:

German words are more likely to end with an unvoiced consonant than are their English counterparts. This is easy to see in cognate pairs such as old/alt, bed/Bett, bread/Brot, red/rot, bridge/Brücke, edge/Ecke, five/fünf , crib/Krippe. Even those German words spelled with a final letter b, d, or g are pronounced with the unvoiced consonants /p/, /t/ and /k/. For example :

Raub (robbery) is pronounced /ʁaʊ̯p/

Bad (bath) is pronounced /bat/

Zug (train) is pronounced /ʦuk/

As a result, Germans speaking English have a general tendency to devoice final consonants in English words.

| RUB | MUD | JUDGE | RUG | EGGS | LOVE | BUZZ |

| /b/→[p] | /b/→[p] | /ʤ/→ [ʧ] | /ɡ/→[k] | /ɡz/→[ks] | /v/→[f] | /z/→[s] |