MODERN RP

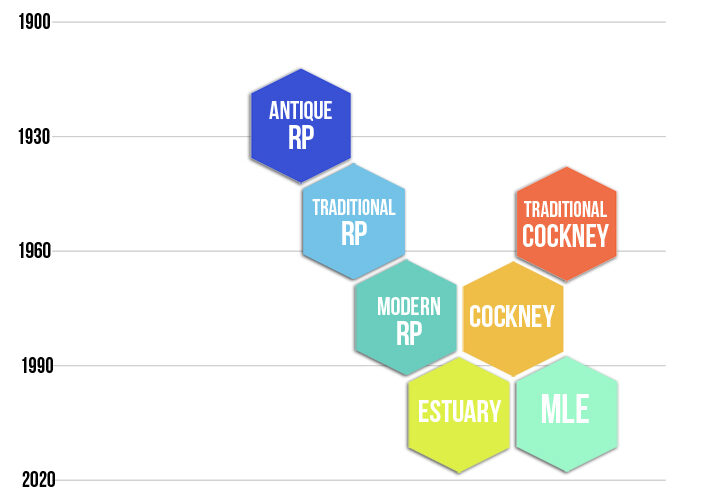

The problem with using the term Received Pronunciation to describe a single accent is that it has been used for more than two centuries. Accents change, and the accent described with this term has changed a great deal over that time. John Walker uses it in 1774 , though he is not so much describing an accent as an accepted pronunciation of particular words. Later in his pronouncing dictionary it’s plain that he defines accepted and received as synonyms. A.J. Ellis uses the term in 1869 to describe the pronunciation…of “pronouncing dictionaries and educated people”. The evidence we have from other sources however, makes it clear that the accent of these “educated people” in England has changed tremendously. So if we use the term RP, we’ll have to do so the same way we use “cc” in reference to emails, as a historic artifact that we’ve decided to live with, but that has lost its original associations. I’ve followed this path of convenience, but with further descriptive terms to specify a particular accent of a particular time, place, and cultural association. Hopefully that will help us avoid the problematic usage of RP referring broadly to the whatever variety is currently accented and in use by those in academic, political, and economic power. I’ve chosen three specifying labels that refer to the evolutions of the accent through three overlapping periods of perhaps 40 years each: Antique RP, Traditional RP and Modern RP.

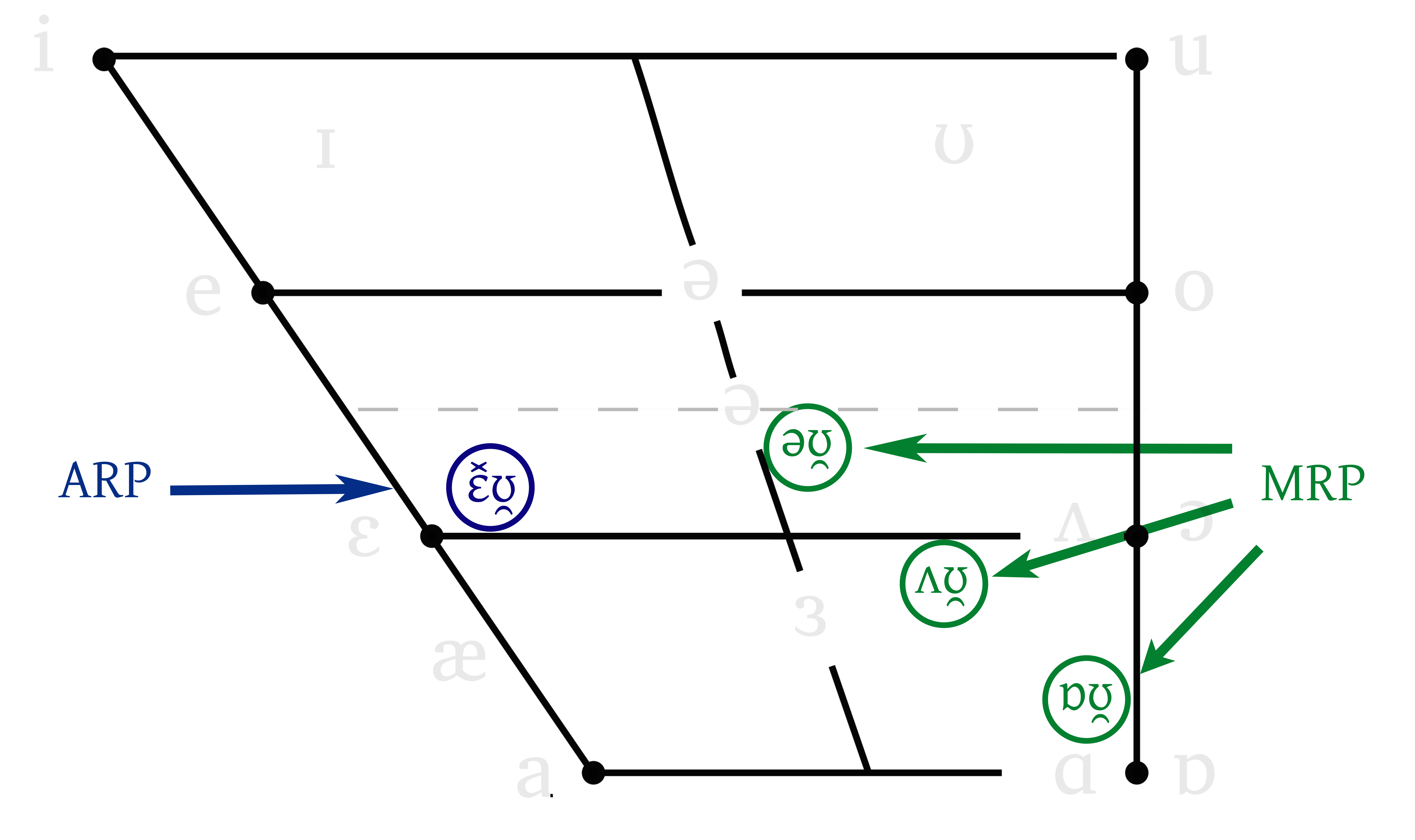

Here’s a chart to help visualize how each of these varieties have given way to new one:

** I’m afraid this chart shows its age, since here we are in 2022 and Modern RP is still going strong. There are also speakers of Traditional RP kicking around, though precious few speakers of Antique RP remain.

Usually, we begin our analysis of an accent with PEOPLE, and the previous section dealt with the broader context of all accents that have been given the name RP. Arguably it makes sense to include discussion of the history of the accent label in this section because PEOPLE is meant to include an understanding of how the speakers of an accent tend to have some shared identity, both in their own understanding and in the views of others. The name RP is certainly part of that understanding, Speakers of Modern RP would most likely simply say that they speak RP if they put any label on it at all.

I’ve chosen to label this particular variety Modern RP, and I do feel that there is some shared identity for the people who speak this way. There is, for any accent, a cultural context which can tell us about the people who speak it, how they view themselves, and how outsiders might view them. The accent coach, Marina Tyndall, whose own accent I would classify as Modern RP recorded the following discussion of the “Grades of RP” for KTS. She uses impressionistic language like “slouchy RP” that conveys her own sense as an insider of what these varieties sound like and what they mean.

As you listen, do your best to let the specifics of sound classification slip past you and focus on absorbing the context:

You may very well be familiar with an older version of this accent which I have labeled Antique Received Pronunciation (ARP). That accent is associated with the strictly enforced class hierarchy of the British Empire at its peak. While sociolinguists might call this a prestige accent, that’s not the same as saying that the accent has any inherent qualities of beauty or superiority. Being the accent of those with power, and those who hoped to get power, it might be read as conveying wealth and erudition, or arrogance and malice. Along with the fall of that empire, came a decline in the social value of ARP. What became socially valuable to a younger generation of speakers is demonstrated by a very rapid shift away from that older form.

Comparing the accents of England’s royal family over the years, it’s surprising how much the accent changed. In a family whose profession it is to maintain a symbolic continuity of social hierarchy, it makes sense to hear more stability in accent through the decades, but when you compare the videos below from four generations of the royal family .When we reach Prince William, it’s clear that there would be no social value for him to use Antique or even Traditional RP.

Once again, it will be useful to begin from a sense of how the older form of the accent felt, and to view Modern RP as a shift away from Antique RP. In that older form, it’s clear that the relative tenseness, and closeness of this accent’s oral posture that are most salient. That is to say, the jaw tends to be held a bit higher than in most American accents, and the lips and tongue tend to carry a slight tension.

This narrower field of play and slight, we could say ‘elastic’ tension means that its speakers are able to speak quickly and with a great deal of articulatory activity. In particular, the tip of the tongue is very active, and the front of the tongue tends to be narrower. The tongue root is more advanced, and front vowels tend to be formed very front indeed. To put this another way, American accents tend to be marked by tongue root retraction and centralization in comparison to RP. The lip corners tend to be very slightly retracted and compressed toward the teeth. However, some phonemes are realized with more rounding than their American counterparts, and so the net effect is of lip corners being pulled gently inward while making fairly frequent flicks forward.

As we shift from Antique to Modern there will be a general relaxation, an opening of the jaw, a retraction of the body of the tongue, and a tendency for the lip corners to remain more forward n general, and to reach quite far forward when called upon.

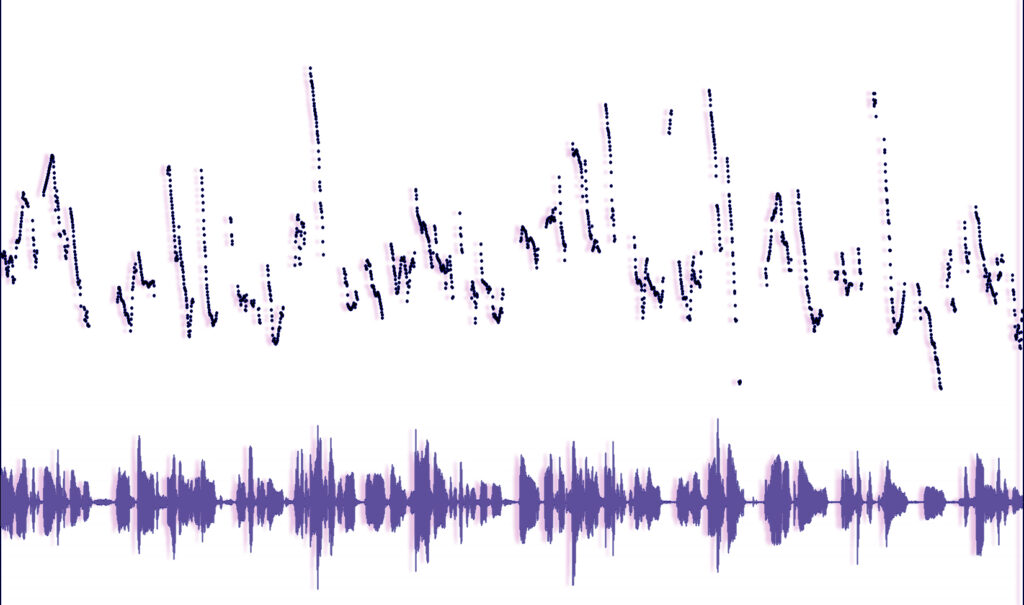

While Modern RP has a bit less of the springy tautness of Antique RP, it will still sound a bit staccato to an American ear. There will also be a greater range of pitch utilized, as well as more abrupt steps up or down in pitch.

RP also uses differences in vowel length for emphasis. All of this leads to a rhythmic pattern described by Gillian Lane-Plescia as “rattle, rattle, bing!” Pitch changes in RP tend to be far more frequent, more simple (rather than compound) and more sudden, occurring quickly across a single syllable in the phrase, rather than occurring gently than across a chain of several words.

The sample below is the pitch information extracted from a sample of a Modern RP speaker:

And the image below shows that information visually:

This is the same sample, but with the pitch track in the right channel and the original recording in the left:

And now, just the passage alone

And here’s Phoebe Waller-Bridge from Fleabag

BATH → ɑː

Take a look at these two sets of words:

A

trap

chat

pal

B

bath

chance

path

Try saying them out loud, first column A, then column B.

If you’re an American, you probably used the same vowel (or pretty close) in all of these words. In RP and in other London accents, the words in these two columns are pronounced with different vowels. For words in column B, where an American would use [æ], an RP speaker will use [ɑː]. Or to use the language of Lexical Sets, BATH words and TRAP words are split in RP. For American speakers, the sets are merged.

For speakers with a merger of this sort, determining which words belong to the BATH set can be challenging. A subset of our broad category of words pronounced with /æ/ will need to be identified and shifted, and running through the list of words, it’s difficult to see any rules that would help in making this distinction.

It may be useful to know that in the 18th Century, most speakers of English categorized these words exactly as a modern American would. It was only after the American Revolution that speakers of English in England began to lengthen the vowel in some cases. This process is called “pre-fricative lengthening,” and it describes a tendency for vowels spelled with “a” to last a little longer when followed by a cluster of fricatives such as “ff, ft, sk, or ss.” Eventually, the lengthened group also began shifting towards a back vowel. As a result, words like “path”, “ask”, or “grasp” are likely candidates to be part of the BATH set. Unfortunately, this is not a perfect predictor of pronunciation. There are words like “grant” or “can’t” that fall into the BATH set, despite their not following this “pre-fricative” pattern, and the words “cant” and “pants” remain in the TRAP set. So, to be sure, a pronouncing dictionary should always be consulted.

Actors who are unsure whether a word belongs to TRAP or a BATH, sometimes hit upon a compromise solution, of pronouncing uncertain candidates with a vowel poised somewhere between these two choices. This is not a happy solution however, because it eliminates the distinction that is a feature of this accent.

The process of pre-fricative lengthening does bring up another point. You’ll notice in the transcription above the vowel [ɑ] is followed with the length symbol [ː]. This indicates that the vowel lasts a bit longer.

We’ve looked at vowel length before, and so we know that the actual durations of vowels vary according to a range of circumstances. What’s important to pay attention to here is that TRAP vowels are short vowels, and BATH vowels are long. Again, that doesn’t mean that there is a required duration , only that under the conditions most favorable to full length (a stressed, monosyllabic word with a voiced continuant consonant following) a BATH vowel is free to get a bit longer than a TRAP vowel.

Listen for the BATH words in this sample:

TRAP → æ

As we’ve already discussed, TRAP words share a similar pronunciation in RP and most varieties of American speech. There are certainly subtle variations, but we can easily think of this vowel sharing the same identity. To put it another way, the TRAP set contains all the /æ/ phonemes remaining after the BATH subset has been removed.

One confounding factor for some American speakers is the possibility (the likelihood?) that you have a split in your TRAP set, realizing some as relatively open monophthongs, and others as more close. Just compare hat, hang, hash, ham and habitat. It would be surprising to me if you used exactly the same vowel realization in all of those words. We might hear a TRAP/TRAM split, or a TRAP/TRASH split, or a HAT/HANG split. We can return to this point when discussing varieties of American accents, but for RP we should be targeting a realization that is definitively front, short, and monophthongal.

In the case of Modern RP, we should target our TRAP vowels fairly open, flirting with a realization as open as [a].

Finally, In addition to the TRAP/TRAM split of American English, there’s another subset of (nominally) TRAP words that many American speakers of English would consider members of the SQUARE set. When the consonant following the vowel is /r/, as in words like carry, Paris, arrow, RP speakers (including J.C. Wells) analyze these words as TRAP+ /r/. Most American accents would categorize these as SQUARE words, pronouncing them with something like [ɛɚ̯]. Unfortunately, the rules governing this pattern aren’t fully predictable. A double “r” in between two vowels is a good indicator. The words arrow [ˈæ.ɹəʊ̯] carriage, [ˈkæ.ɹɪʤ], and marry [ˈmæ.ɹɪ] all fit the TRAP + /r/ pattern in RP. When it comes to a single ‘r’, though, things aren’t as predictable:

TRAP + /r/

Paris [ˈpæ.ɹɪs]

marry [ˈmæ.ɹɪ]

Arab [æ.ɹəb]

SQUARE

parent [ˈpɛɚ̯.ɹənt]

Mary [ˈmɛɚ̯.ɹɪ]

area [ˈɛɚ̯ɹi.ə]

LOT – CLOTH – THOUGHT

→ ɒ → ɒ → ɔ̝ː

The three lexical sets covering the low back vowels are LOT, CLOTH, and THOUGHT. Looked at together, we can think of these sets as overlapping brackets allowing us to note the distribution of these vowels along a scale of length and roundness. In Western American English, we might see all of the words in these categories pronounced with an unrounded, and not particularly lengthened [ɑ]. My own, Midwestern accent separates LOT [ɑ] from CLOTH/THOUGHT [ɒː]. For Traditional and Modern RP, LOT and CLOTH form a single, merged category of words with [ɒ] and THOUGHT is a separate category realized with [ɔ̝ː].

Here’s Mohsin Butt with examples of LOT and CLOTH:

research fellow exploring a novel microbiological marker across … across Pakistan. I was not at all disappointed. They’re incredibly hospitable people

Compare those vowels with the THOUGHT vowels here:

Now, you may have noticed, in the previous recording, that the words fourth and before had essentially the same vowel as sought or talk despite the fact that they would be pronounced in most American English with a noticeable /r/. This is because London accents are nonrhotic. We’ll come back to that idea in a bit, but for now, notice that talk and torque would sound the same.

Here’s another sample with a few more of these:

learned how to order in our resources cupboard. I learnt how to record data, making sure that it was in a presentable format..

PRICE → äɪ̯

FACE → ɛ̈ɪ̯

These two diphthongs are not wildly different from their realizations in the US. They’re placed together here because they are both somewhat more open and back than their US counterparts.

PRICE

FACE

away from gastroenterology, and investigate the relationship between data collected from patients for our study investigating latent TB infection.

GOAT → əʊ̯ ʌʊ̯ ɒʊ̯

In the first half of the 20th Century, this diphthong made a rapid shift forward. For some speakers, the nucleus of the diphthong went as far as / ɛ̈ /. That fronted position is a strong marker of Antique RP so we should be careful to avoid that extreme. The shift toward Modern RP has, in some ways been a matter of blending with Cockney, and that means that many speakers will use the variable pronunciation from Cockney known as GOAT allophony.

To state it more simply, the possible of realizations of GOAT can cover a wide range:

Although Dr. Butt has some features of an older form of RP, you can hear some variability in his GOAT realizations.

conduct a study for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis. We also wrote ethical approval forms and had those approved.

Here’s a version of the same sample with the GOAT diphthongs extended:

And here are some more examples:

Emma Watson (Modern RP)

David Beckham (Estuary)

RHOTICITY → Ø

NEAR→ nɪə̯ SQUARE→ skʍɛ̞ START→ stɑːt NORTH→ nɔːθ CURE→ kçɔː lettER→ ˈlɛtә NURSE→nɜːs

As noted in the section on THOUGHT, the vowels of FORCE and THOUGHT are identical. The two categories have merged into one. That’s because this accent is non-rhotic, which means that when an /r/ phoneme occurs directly after a vowel in the same syllable, it isn’t pronounced.

There are some further complications we’ll need to examine, but

[notice the similarity between START words, and the vowels in “Butt” and “Pakistan”]

[the word sure belongs to the CURE category, but you can hear that it has merged with NORTH/FORCE/THOUGHT]

NURSE → ɜː ɛ̽

In the sample below, you can hear Queen Elizabeth pronouncing NURSE words with a vowel so far forward as to nearly arrive at [ɛ]:

lettER → ˈlɛtə͡ ɹɪz ˈlɛtə tu

JC Wells laid out both commA and lettER sets to account for the fact that in a non-rhotic accent of English, commA and lettER words end in the same sound. Nevertheless, they are identical realizations of different phonemes. Words in the lettER set, like Peter or tuner sound exactly like pita or tuna , but because of the underlying /r/ phoneme, those words would behave differently when immediately followed by a vowel. Peter is would be pronounced [ˈpitə͡ ɹɪz], but Peter says would be pronounced [ˈpitə. sɛz].

in this sample, you can hear Dr. Butt linking lettER words to the subsequent vowel with an /r/ except between order and and. In that case, he makes a tiny gap in the continuity of the ideas, and that’s enough to leave out the connective /r/ phoneme.

commA → ˈkɒmə͡ ɹɪz

In MLE, Cockney, and Modern RP, both commA and lettER would occasion this linking /r/, even though commA has no underlying /r/. This is called an intrusive R. Dr. Butt has one example of this when he says “Dr. Sidra and I” The final vowel of “Sidra” sounds like it could represent a missing /r/ phoneme, and so a link is automatically provided.

This can occur whenever a final vowel sounds like it could be a non-rhotic diphthong.

Ska is a kind of music Scar is a character in Lion King

Leah isn’t happy Lear is mad

Fiona Shaw acts The shore acts as a barrier

DUKE → djuk→

There is a subset of words in the GOOSE set that begin the /u/ vowel with a /j/. This difference between /u/ and /ju/ has to do with the history of these words and how they’ve changed over time. This is why “mute” and “moot” have a different pronunciation. However, we can usually tell which words are in this /ju/ subset because of the consonant that precedes the /u/. Most English speakers put “beauty” and “music” and “fume” in this category — we don’t do this with “booty” and “mood” and “food”, but that’s because they have a different history, as indicated by their spelling.

RP has a more expansive category of GOOSE+ j words. These include duke, and tune and new. Antique RP is even more expansive and includes lute and suit but a Modern RP speaker would be less likely to do so.

| beauty | bjuti | |||

| music | mjuzɪk | |||

| few | fju | |||

| new | nju | |||

| duke | djuk | ʤuːk | ||

| tune | tjun | ʧuːn |

BETTER BRITISH WRITER

Intervocalic /t/ is unvoiced, and aspirated. This is in contrast with most speakers of American English who use an unvoiced, or at least unaspirated /t/. Of course, many words have medial /d/ in both RP and American accents, so one should be careful not to generalize the rule to the devoicing and aspirating of all such sounds. RP speakers pronounce “Betty” as [ˈbe̞tɪ] but they don’t pronounce “ready” as [ˈɹe̞tɪ]. Modern RP differs from older RP in that /t/ is often given a bit of reinforcement by a glottal stop : /t͡ʔ/

Some Calisthenics

Even after mastering individual realizations of phonemes, is still be a challenge to execute a particular sequence because of the athleticism of the tongue movements, or because the targets aimed at by the accent seem counter to our own accent intuitions. For that reason it’s useful to practice particularly challenging sequences in order to develop ease and agility.

I thought you brought hot coffee to father.

Roger’s daughter was dancing and walking on rocks.

Please understand—you cannot demand that I clasp your hand.

Can the cast eat that vast vat of pasta? I plan to pass.

Shibboleths

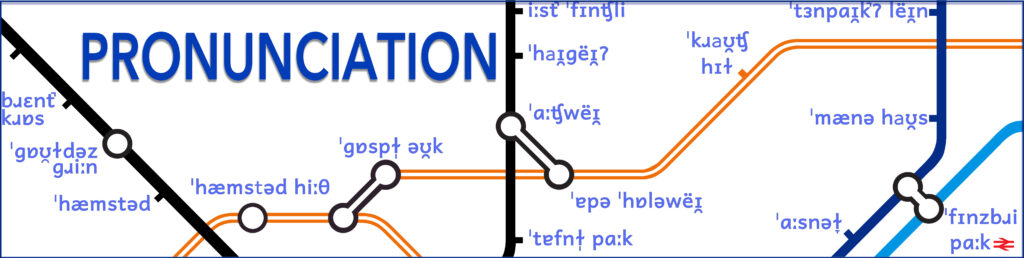

There are a number of words and proper names whose standard RP pronunciation differs from the standard American one. In the case of names, especially, these pronunciations are often wildly counter-intuitive. When in doubt, ask someone who knows or look it up. A (very partial) listː

figure /ˈfiɡə/

clerk /klɑːk/

herb /ɜːb/

lieutenant /lɛfˈtɛnənt/

controversy /kənˈtrɒvəsɪ/

privacy /ˈpɹɪvəsɪ/

schedule /ˈʃɛdʒʝuɫ/

vitamin /ˈvɪtəˌmɪn/

urinal /jʊə̆ˈɹaɪnɫ̩/

garage /ˈɡæˌɹaːʒ/ or /ˈɡæɹɪdʒ/

process /ˈpɹəʊsɛs/

program /ˈpɹəʊɡɹæm/

leisure /ˈlɛʒə/

zebra /ˈzɛbɹə/

(the letter) Z /zɛd/

aluminium /ˌæljʊˈmɪnɪəm/

detail /ˈditeɪ̆ɫ/

simultaneous /ˈsɪmˡl̩ˌteɪ̆njəs/

cigarette /ˌsɪɡəˈɹɛt/

lever /livə/

tissue /ˈtɪsju/

issue /ˈɪsju/

missile /ˈmɪsaɪ̆ɫ/

mobile /ˈməʊ̆baɪɫ/

futile, , etc. /ˈfjutaɪ̆ɫ/

ballet /ˈbæleɪ̆/

brochure /ˈbɹoʊ̆ʃə/

valet /ˈvælɪt/ or /ˈvæleɪ̆/

comrade /ˈkɒmɹeɪ̆d/

cafe /kæf/ or /ˈkæfeɪ̆/

corollary /kəˈɹɒləˌɹɪ/

ate /ɛt/

yogurt /ˈjɒɡət/

debris /ˈdɛbrɪs/

premature /ˈprɛməˌtçʊə/

glacier /ˈɡlæsjə/

St. John /ˈsɪndʒən/

Hertford /hɑːfəd/

Pall Mall /pæl mæl/

Warwick /ˈwɒɹɪk/

Gloucester /ˈɡlɒstə/

Leicester /ˈlɛstə/

Beaulieu /ˈbjulɪ/

Beauchamp /ˈbiːtʃəm/

Caius /kʰiːz/

Magdalen /ˈmɔdlɪn/

Belvoir /ˈbivə/

Derby /ˈdɑbɪ/

Marlborough /ˈmɔːlbɹə/

(Caius, Magdalen are colleges at Cambridge and Oxford. Beauchamp and Belvoir are castles, and also common street names.)